Quantum Computers Tackle Simulating Quarks

December 11, 2025

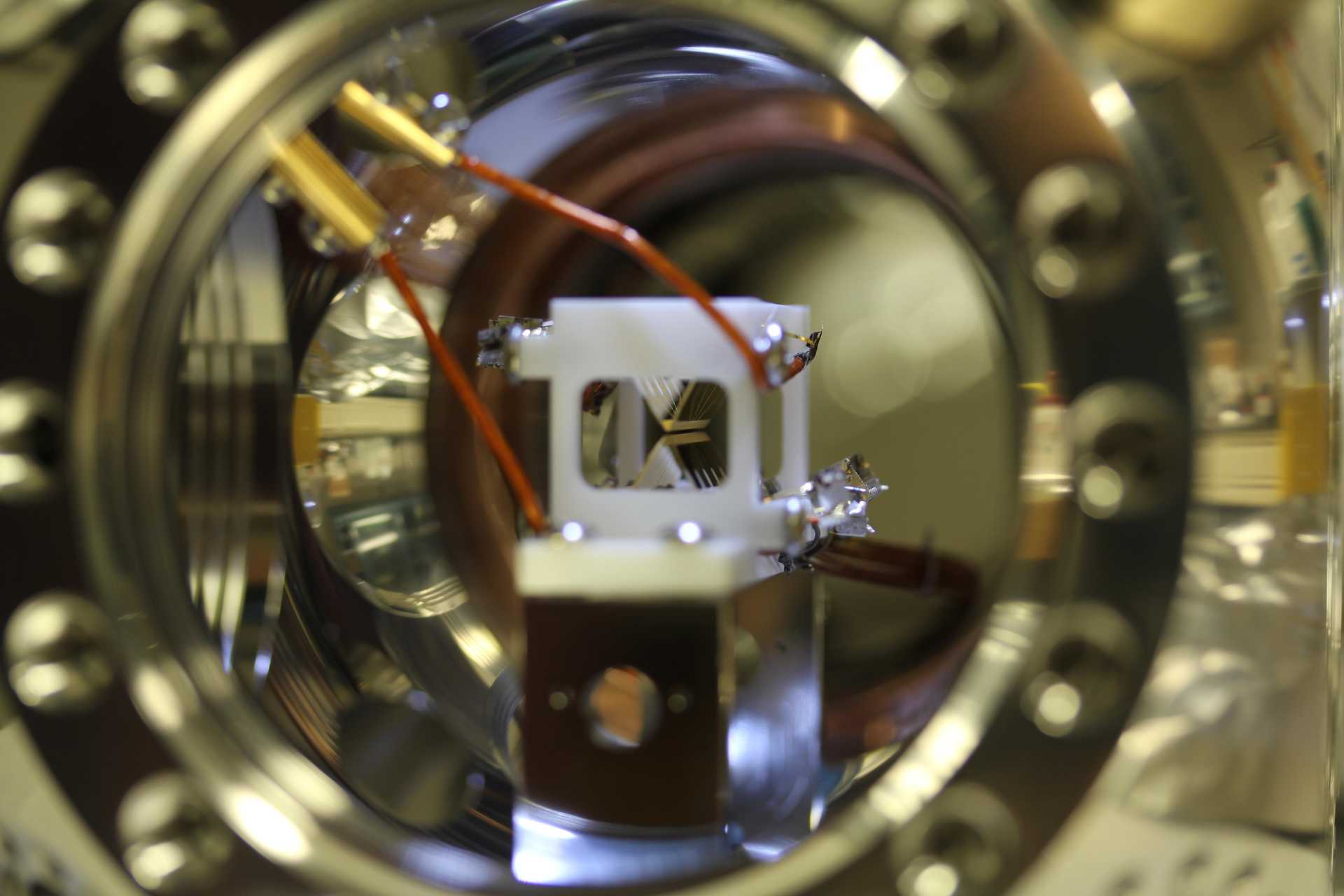

An ion-trap that can be used to hold electrically charged atoms and manipulate them as the basic building blocks of a quantum computer. In a new experiment, researchers used a trapped-ion quantum computer to simulate a one-dimensional model of how quarks and other particles behave. (Credit: JQI, Shantanu Debnath and Emily Edwards)

Researchers at JQI and their colleagues have reached a milestone in quantum information science: using a quantum computer to simulate how matter can behave in extreme environments, like the early universe after the big bang.

The researchers simulated a one-dimensional version of a theory called quantum chromodynamics. The theory helps researchers describe how quarks—the particles that make protons and neutrons—interact at various combinations of matter density and temperature. The researchers shared their results in an article published in the journal Nature Communications on Nov. 21, 2025.

“The stability of all matter is based on this theory and describes how quarks ‘talk’ to each other,” says Christine Muschik, a University of Waterloo’s Institute for Quantum Computing (IQC) faculty member and professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Waterloo. “At IQC, we developed a new theoretical and experimental approach as a tool for quantum computation.”

JQI Fellows Norbert Linke and Alaina Green and members of their labs ran the simulation on a trapped-ion quantum computer. The collaboration also included JQI graduate student Anton Than and IQC postdoctoral fellows Abhijit Chakraborty and Yasar Atas, who were co-lead authors of the paper, as well as Randy Lewis at York University.

“There is so much about nature that we just don’t know,” Chakraborty says. “We can write a set of equations to describe a system but understanding how the system behaves under different parameters is another story. For large, dense physical systems like in the early universe, we need to control parameters such as temperature and density, and our new method delivers both.”

To make this simulation possible, the team introduced two key innovations. The first adds a process after the simulation is complete, without adding computing power, to make sure the results follow nature’s fundamental symmetry rules. The other method encodes information into the natural motion of ions, which typically isn’t used for quantum information processing. This new approach makes more efficient use of existing quantum resources: by doubling the register size available for computing, it can process more complex algorithms.

"We are looking forward to discovering more quantum computing applications which will benefit from the greater computing power afforded by the use of the motional ancilla," Green says. "While motional ancilla are not a suitable stand-in for any qubit, we suspect there will be more algorithms like the one in this paper, for which a fully-fledged qubit is overkill and our motional ancilla will serve. The basic idea is that there's no sense in paying for a Cadillac qubit if the much cheaper toy truck will work just as well."

This research demonstrates the creativity involved in pushing the boundaries of existing quantum technologies. Quantum computing has been forecast to have great potential, but innovative theoretical work and simulations of theories like quantum chromodynamics are only now demonstrating just how useful quantum computers can be in shaping the future of technology and fundamental scientific discovery.

“It’s clear that simulating certain problems in particle physics works very well on classical supercomputers, and it’s a highly successful field,” Muschik says. “But for physics that is trying to understand how multiple particles interact with each other, like in quantum chromodynamics, classical computers are fundamentally roadblocked, so a quantum computer is needed. Otherwise, a huge class of problems keeps modern physics stuck.”

This text has been adapted with permission from a story originally posted by the Institute for Quantum Computing at the University of Waterloo.

In addition to Linke,, who is also the IonQ endowed professor of physics at UMD, the director of the National Quantum Laboratory (QLab) at UMD, and a senior investigator at the National Science Foundation Quantum Leap Challenge Institute for Robust Quantum Simulation; Green, who is also a physicist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology; Muschik; Than; Chakraborty; Atas and Lewis, co-authors of the research paper also include UMD graduate students Matthew Diaz and Xingxin Liu; JQI undergraduate research assistant Kalea Wen; and Jinglei Zhang, who is a Research Associate at the Institute for Quantum Computing, University of Waterloo.

Experts

People

![a woman smiling at the camera and wearing a red turtleneck]()

Alaina Green

NIST Physicist

Groups

JQI